Meelis Maripuu, Ülle Kraft

Estonian war refugees as a whole represented a diverse cross-section of society. The most clearly defined group among them was the more than 7,000 coastal Swedes, who were also among the first to leave.

The largest wave of departures of Estonians from their homeland began in 1943 from Estonia’s northern coast to Finland. The greater portion of these particular refugees (about 3,500) were men who were accepted to serve in the Finnish Army when they arrived on the other side of the gulf. Alongside men, at least 500 women and children also left Northern Estonia for Finland. In the autumn of 1944, they were forced to flee onward to Sweden due to fears of being extradited to the Soviet Union. Together with refugees from the last phase of the war, at least 5,000–7,000 Estonian war refugees reached Sweden via Finland.

Mass exodus from Estonia began in August of 1944 and lasted until the start of October when the Red Army gained control of most of the coast of Saaremaa. Germany and Sweden became the two primary destination countries for the war refugees. The latter half of September was the high point of the exodus in both directions. That is when the German fleet organised evacuation from Tallinn, and a flood of refugees fleeing on their own headed for Sweden on board all manner of seagoing vessels. According to hitherto available information, nearly 80,000 Estonians in total lived abroad in the first postwar years, most of them in Germany and Sweden.

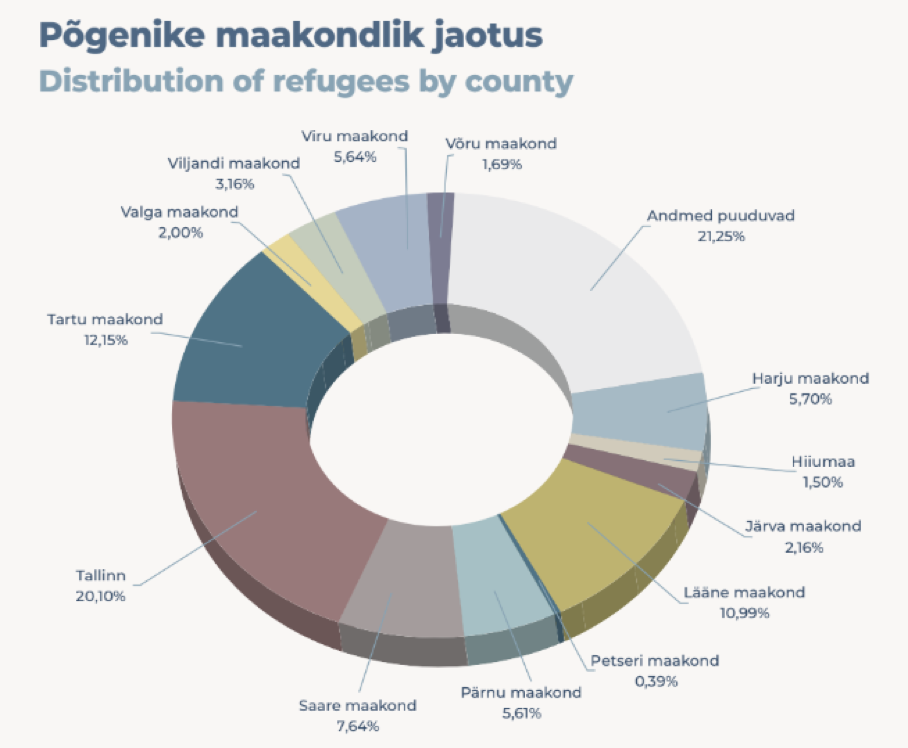

The following overview is based on data concerning nearly 65,000 refugees, whose personal data has hitherto been ascertained together with their previous places of residence. In divergence from the administrative divisions of that time, residents of Tallinn have been separated from Harju County and the rural municipalities of Hiiumaa have been separated from Lääne County in the interests of comprehensiveness.

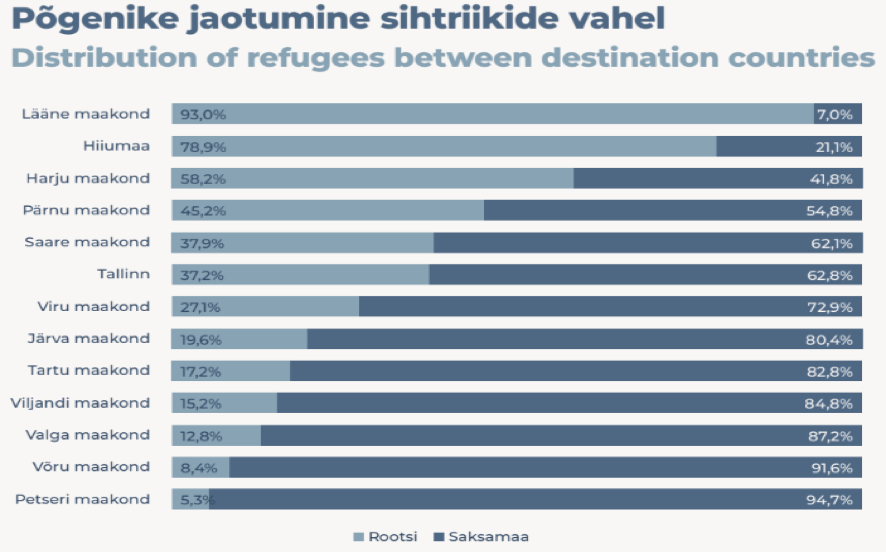

There were at least 37,000 Estonians (nearly 60% of Estonian refugees) in various parts of Germany at the end of the war. Two sizable groups that emerge are civilians who the German authorities evacuated by sea on board large ships, and Estonian men who had retreated to Germany in the ranks of German armed units.

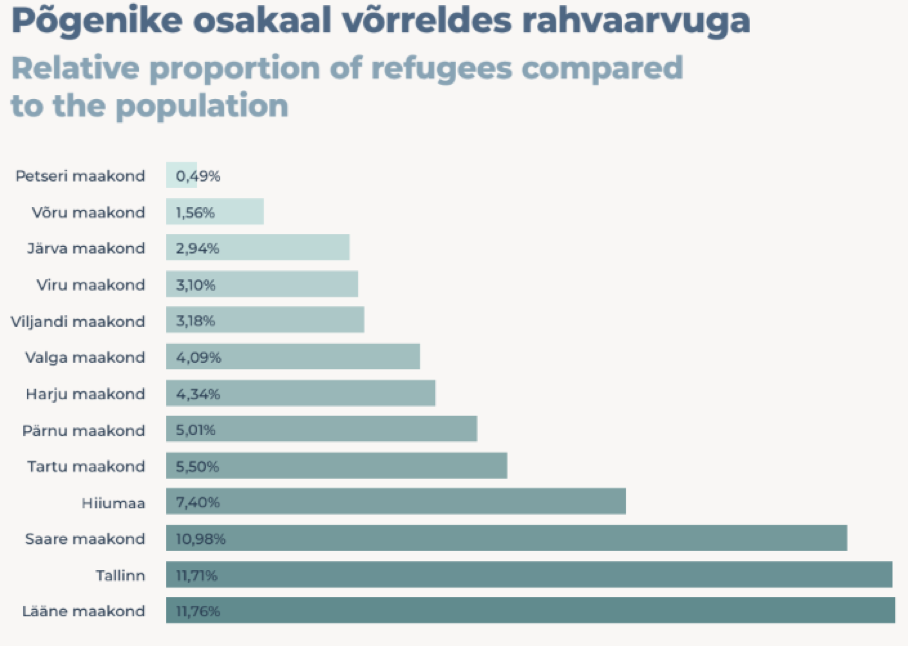

A numerically smaller portion of refugees, more than 26,000 (over 40%), reached Sweden. Among them were most of the coastal Swedes, who crossed the sea with the permission of the German authorities. The rest of the refugees had to defy the bans of the occupying authorities and brave the stormy sea. Although Sweden was the most preferred destination country for the majority of the refugees, it was not easy for people living farther from the coast to find places for themselves in boats that departed secretly. People living on the coast had a better chance to get to Sweden. The greater relative proportion of refugees that went to Germany in the case of refugees from Saaremaa is due to the forced evacuation to Germany of approximately 2,500 inhabitants of Sõrve, which is reflected in the statistics.

The numerically largest quantity of refugees left from Tallinn, which can be explained by the city’s larger population and the relative ease with which people could depart on board German evacuation ships. The second largest number of refugees went from Tartu, Estonia’s second city in terms of size, together with Tartu County, followed thereafter logically by the islands and the Western Estonian coast. The reason for the relatively larger number of refugees from Lääne County is clearly the departure of almost the entire coastal Swedish ethnic group from Estonia.

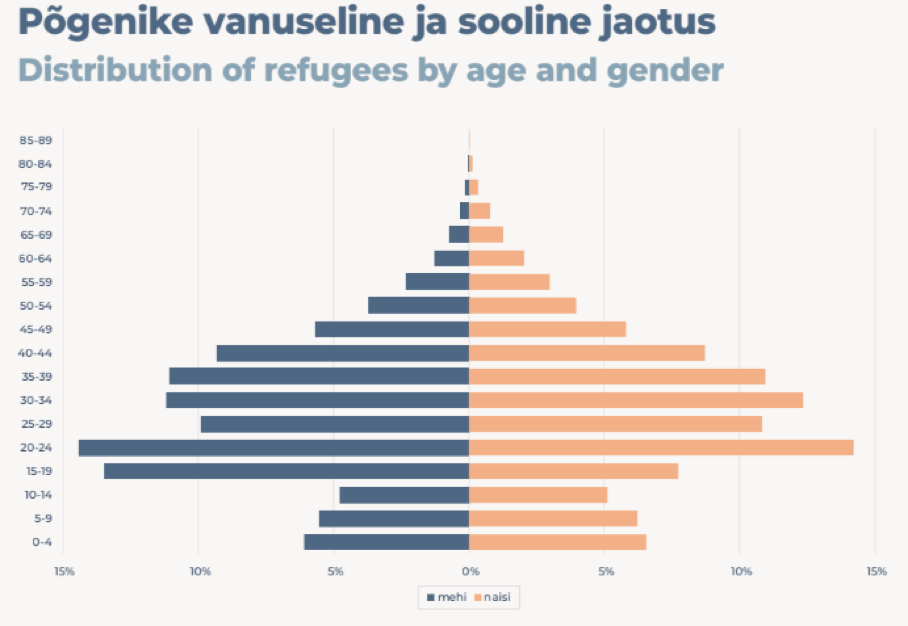

A deviation can be highlighted regarding the primary distribution of refugees by gender and age. The larger relative proportion of men aged 15–20 years compared to women in the same age range stands out. This can be explained by the proportionally larger rate of departure from the homeland of young men who were serving in the German armed forces. Immediately after the war, at least 10,000 people who had left their homeland in the course of the events of the war returned to Estonia for various reasons. For the most part, that could be connected with familial reasons, but Soviet propaganda also had its role. The vast majority of refugees did not consider it possible to return to Estonia while it was occupied by the Soviet Union. They remained in the West, initially hoping for the quick liberation of Estonia. The international situation, however, did not allow that. The Estonians in Germany largely had to find new places of residence for themselves in other countries. The largest communities of Estonians took shape in Sweden, Canada, the United States, Australia, and Great Britain.

Compared to the prewar population, the proportion of refugees relative to the population was the largest in Lääne County, which is once again due to the departure to Sweden of the coastal Swedish community. Almost just as large a part of the population also fled from Tallinn. The evacuation operation organised by the German authorities from 16 to 22 September largely enabled this. The next largest proportion is from Saare County, where the relative proportion of refugees is presumably somewhat larger than that depicted in the graph. Deficient data on places of residence has not allowed this to be ascertained yet. The share of refugees from Viru County should also be proportionally larger but this too has not yet been ascertained due to deficient data on places of residence.